Many rape kits go untested in Canyon County

Published at | Updated at

NAMPA – Dozens of rape kits in Canyon County sit on shelves untested.

In Idaho, state law does not mandate every rape kit be tested. Instead, the fate of a kit and whether it will be tested is at the discretion of each law enforcement agency handling the case.

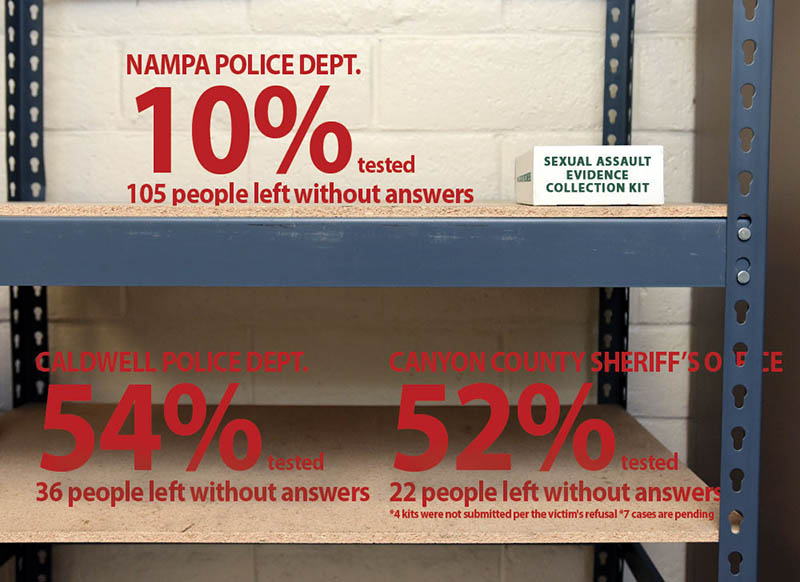

The result is that the number of kits that get tested varies widely among different law enforcement agencies, from 10 percent in Nampa to 54 percent in Caldwell.

“A lot of the decision is left up to the individual detective,” Nampa Police Chief Craig Kingsbury said.

A look at local numbers since 2010 shows:

- At the Nampa Police Department, about 10 percent of the kits collected were submitted for testing.

- In the Caldwell Police Department, about 54 percent of kits collected were sent in and tested.

- In the Canyon County Sheriff’s Office, about 52 percent of kits collected were sent in for testing.

In Idaho, if law enforcement determines no crime has been committed or the case is no longer being investigated as a crime, the kit may not be sent to a laboratory for testing.

Additionally, kits are not submitted for testing if a victim decides he or she does not want the kit tested.

Federal law does not mandate all rape kits be tested, but 10 states have laws mandating rape kit testing.

The Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network estimates that every 107 seconds, an American is sexually assaulted. Each year, that totals about 293,000 victims of sexual assault in the United States.

Canyon County rape kit collection

According to records collected from public records requests made by the Idaho Press-Tribune:

- The Nampa Police Department collected 117 rape kits into evidence from Jan. 1, 2010, to Oct. 5, 2015. Of those, 12 rape kits were sent to a lab for testing.

- The Caldwell Police Department collected 79 rape kits into evidence from Jan. 1, 2010 to Sept. 30, 2015. Of those kits, 37 were sent to a lab for testing, 10 were sent but not tested, 26 were never sent and six are currently at the lab.

- The Canyon County Sheriff’s Office collected 46 kits into evidence from Jan. 1, 2010 to Sept. 30, 2015. Of those kits, 24 were sent to a lab and tested.

Of the 22 kits not submitted by the sheriff’s office, two cases were referred to another agency, five had no charges filed, four were determined by law enforcement to be unfounded, four kits were not submitted per the victim’s refusal and seven cases are pending.

The Parma Police Department collected two kits and tested both.

The Wilder Police Department collected one kit, but it was not tested after both parties involved claimed the sex was consensual.

The Middleton Police Department has not collected any rape kits, but the agency has been active only since Oct. 1, 2014.

The issue is not limited just to Canyon County.

- The Twin Falls Police Department collected 84 kits between Jan. 1, 2010, and Nov. 3, 2015. Of those kits, 19 were sent to a lab for testing, or 23 percent.

- The Idaho Falls Police Department collected 150 kits between Oct. 4, 2010, and Nov. 4, 2015. Of those kits, 65 were sent to a lab for testing, or 43 percent.

Deciding what goes

The process of deciding which kits are tested has been discussed by officials within the last year.

Last year, a panel of experts met to discuss the best policies for processing sexual assault kits in Idaho, according to Matthew Gamette, laboratory system director for the Idaho State Police Forensic Services laboratory in Meridian. In turn, law enforcement is required to follow those policies.

The panel included representatives from the Idaho Supreme Court, state and local law enforcement, the state ISPFS forensic lab, victim advocates, prosecutors, a public defense attorney, doctors, nurses, hospitals, clinics and victim compensation experts.

Through that approach, the panel decided that the submission of those sexual assault kits should include law enforcement discretion and a victim’s right to choose whether the kit be tested.

“We considered victim rights, public safety, court issues, law enforcement challenges, (Combined DNA Index System) rules, lab processes and many other things in our deliberations,” Gamette said in a letter to Nampa and Caldwell police departments. That information was sent to the Idaho Press-Tribune through the Caldwell and Nampa police departments’ attorney, Maren Ericson, of Hamilton, Michaelson, & Hilty, LLP.

Nampa Police Chief Craig Kingsbury said the decision on whether to send in a rape kit for testing is a case-by-case decision.

Of the 105 cases in which a rape kit was not submitted in Nampa since 2010, without looking at each case, Kingsbury said he couldn’t comment on whether Nampa’s number of untested kits was alarming.

Circumstances in the decision not to test a kit may include whether the victim and suspect knew each other, according to Kingsbury. Rape kits related to a case where the suspect is a stranger are always sent in, Kingsbury said.

If the case is not going to be prosecuted, the kit may also not get sent in, he said.

Kingsbury said the detectives work with the prosecuting attorney’s office about the decision to send the kit in for testing, as well. The case still could go to court without a rape kit being tested.

Kingsbury said there are also concerns about the wait for getting DNA results back and about submitting DNA that won’t be used. Those are some of the reasons he believes law enforcement should maintain discretion over whether a kit is submitted.

“If we overload the system with DNA that isn’t going to have any effect on any case, that will slow cases down that will be submitted,” Kingsbury said.

Just because a rape kit is never tested does not mean the case couldn’t be tried in court.

Additionally, Kingsbury questioned if it would be a violation of the suspect’s rights to file the DNA into a national database if they were never charged with a crime.

When an alleged victim walks into the police station, said Caldwell Police Chief Chris Allgood, that person is automatically treated as if the claim is truthful. Allgood said intense investigation must happen before police question the truthfulness of an allegation.

“Every rape report is treated as if it’s the real deal,” Allgood said. “The procedure at the beginning is every person is given the opportunity to have a sexual assault kit performed. We don’t ever judge up-front if it’s real.”

As the case develops, sometimes police find inconsistencies or it becomes he-said/she-said testimony, Allgood said.

Canyon County Deputy Prosecutor Erica Kallin said rape kits can corroborate a victim’s version of events during the incident if the question in the case is not who the suspect is, but if the sex was consensual.

As a prosecutor, Kallin said, she cannot interfere with what evidence is or is not submitted for testing.

“The decision to submit a rape kit is 100 percent law enforcement,” Kallin said.

However, in cases where Kallin may have a confession, the rape kits are not as vital to the case, she said. Kallin supervises the prosecutor’s office’s special victims unit.

“I believe there should be some discretion,” said Allgood on whether all kits should be tested. “Some cases turn out to not be a true rape or it turns out there was inconsistencies that turn out to be true.”

If a kit is tested, the suspect’s DNA is put into a database.

“I don’t want to put their DNA on file if a crime was not committed,” said Allgood.

The lab

The Idaho State Police Forensics Services lab in Meridian analyzes all of the kits Idaho local law enforcement collects, with the exception of those sent to the FBI lab. The testing is paid for through state and federal money the lab receives.

The lab has no control over whether local law enforcement agencies submit rape kits for testing. According to the Idaho State Police Forensic Services lab, any individual whose DNA is kept on file in a database in Idaho is not public record. Even police agencies in Idaho do not have direct access to the names of individuals who may have DNA on file in the lab. That would include both the DNA of the alleged victim and DNA of the suspect.

In Idaho, the only people who have access to the list of DNA profiles are DNA scientists at the state lab, said Gamette. If the lab were to find a match in its database regarding a sample, the scientist would then notify law enforcement with the suspect’s name and profile.

In most reports, Allgood said, once information and testimony are gathered, the officer submits the case to the prosecuting attorney. It is then the prosecuting attorney’s decision on whether to charge the accused.

Allgood said sometimes the challenge is not only determining what happened but also what can be proven in court.

Kallin said that in some cases, credibility issues can be in part resolved with the rape kit, noting that the exam itself is as important as DNA evidence collected.

“There are times we will find trauma to the vagina,” she said. “That oftentimes is every bit as important (as DNA).”

Sexual assault kits preformed on children often make a difference in prosecution, as well.

“I think in Canyon County we are very lucky because (detectives) have good judgment and I rely on it a lot,” said Kallin. “We have a lot of amazing detectives.”

She said, however, that the quality of detectives is not the same everywhere else.

Submitting the kits

Each law enforcement agency is responsible for submitting kits related to cases it is investigating, said Gamette. ISP only tests kits that are submitted to the lab.

Gamette’s lab, based in Meridian, is responsible for testing rape kits submitted by law enforcement with the exception of those that are shipped to the FBI lab in Quantico, Virginia. ISP uses the FBI lab for assistance in criminal evidence testing, like many other states, in an effort to reduce backlog.

The current backlog, as of Oct. 29, at the ISP lab was 28 kits, meaning those kits have been at the lab for more than 30 days.

However, that number does not include the kits local law enforcement never submitted.

The oldest kit at the lab that is currently not assigned to be worked on came to the ISP lab July 16. Therefore, as of Oct. 29, the oldest backlogged and currently unassigned kit at the lab has been there for 105 days.

In 2014, ISP completed testing for 93 kits. As of Sept. 22, the lab had completed 95 rape kit tests this year.

In 2014 and 2015, the FBI lab had tested 176 rape kits from Idaho, Gamette said.

One challenge the lab would face if testing of the kits were to become mandatory is that all samples of DNA found in a rape kit would be submitted to a national registry.

The registry is used to cross-reference other kit results in case one suspect’s DNA were to match the DNA found at another crime.

For example, Gamette pointed out that rape kits taken after an alleged sexual assault between a husband and wife don’t always get submitted because the suspect is known.

“In that kind of case, the DNA evidence is not going to be huge contributor at trial. Neither of them will dispute it’s (the husband’s) semen,” Gamette said. “The law enforcement agencies weren’t submitting them at the advice of prosecutor. But, what if he not only assaulted his wife, he’s done something somewhere else and we weren’t processing it into national database? Then that evidence should go into the database.”

The suspect in that case, however, would question why his DNA is going into a national database if it is found to be non-criminal sex, Gamette said.

According to a 2005 National Crime Victimization Survey, approximately 73 percent of rape victims know their assailant.

“There is a concept of test smart versus test all,” he said. “We’re on test smart. Test what’s going to be able to help in a way to (not) victimize the victim again. We don’t want to set up a system where a victim is afraid of them and will not report because they’re of afraid of what happens to their kit.”

While the goal turnaround time on ISP rape kit testing is 30 days, it varies from 30 to 60 days. Due to staffing, the current turnaround for ISP rape kit testing is closer to six months, Gamette said.

The second installment of this series will discuss what advocates, legislators and law enforcement think about current rape kit testing laws.

This story was originally published in the Idaho Press-Tribune. It is used here with permission.

EastIdahoNews.com comment boards are a place for open, honest, and civil communication between readers regarding the news of the day and issues facing our communities. We encourage commenters to stay on topic, use positive and constructive language, and be empathetic to the feelings of other commenters. THINK BEFORE YOU POST. Click here for more details on our commenting rules.