Local man working to preserve 133-year-old cabin and turn it into historical landmark

Published at | Updated atLABELLE – About four miles northwest of Rigby in the rural community of Labelle lies a 263-square-foot-log cabin dating back to 1888.

Keith Harrop, whose great-grandparents helped settle the area and lived in the house, tells EastIdahoNews.com it’s sat untouched for at least 60 years and he’s hoping to preserve it as a historical landmark.

“We’re trying to investigate to see what our options are. We’re thinking of contacting the Jefferson County Historical Society and have them come and look at it (to learn what we can do),” Harrop says.

He and members of his family began the initial work several weeks ago by removing trees and brush that had grown around the house and grinding away stumps. They also spent time removing old items inside the home, which included an old washer and dryer, bathtub and other items. It’s been used as a granary, and most recently as a barn, which made a mess of the floors.

After clearing away the debris, Harrop discovered a rotting log on the cabin’s foundation. As the project moves forward, Harrop says this will be one of many things that need to be repaired to ensure the structural integrity continues to hold up for future generations.

Harrop grew up on the property adjacent to where the cabin sits. He moved to Illinois after getting married 45 years ago. Just a few years ago, he retired and moved back to Rexburg and visited the cabin with his grandson.

“As we came, I felt a reverence that I can’t describe and he did, too. Ever since then, I’ve felt driven to do what we can to preserve the cabin,” Harrop explains.

A ‘beautiful’ wilderness of water

Cyrus Rostan and Sarah Smitties were part of a small group of people who settled what is now Labelle (which is a French word meaning “beautiful”) in 1884. They had heard about the Snake River and wanted to start a new life in a wilderness full of water. At that time, the entire desert landscape was covered with sagebrush.

Harrop says they came from Millcreek, Utah and filed a declaration of homestead, which meant they’d get a deed from the government if they cleared and improved the land.

“In my Grandma Rostan’s history, she said they hooked three teams of horses on a railroad tie and drug it across the field to rip out the sagebrush. At night, they would pile up all the sagebrush and burn it,” says Harrop.

Over the next several years, they worked the land. During that first year, Harrop says they cleared 101 acres of sagebrush. They went to Missoula, Montana the following year to earn money working on the railroad before coming back to Labelle to plant crops the next summer.

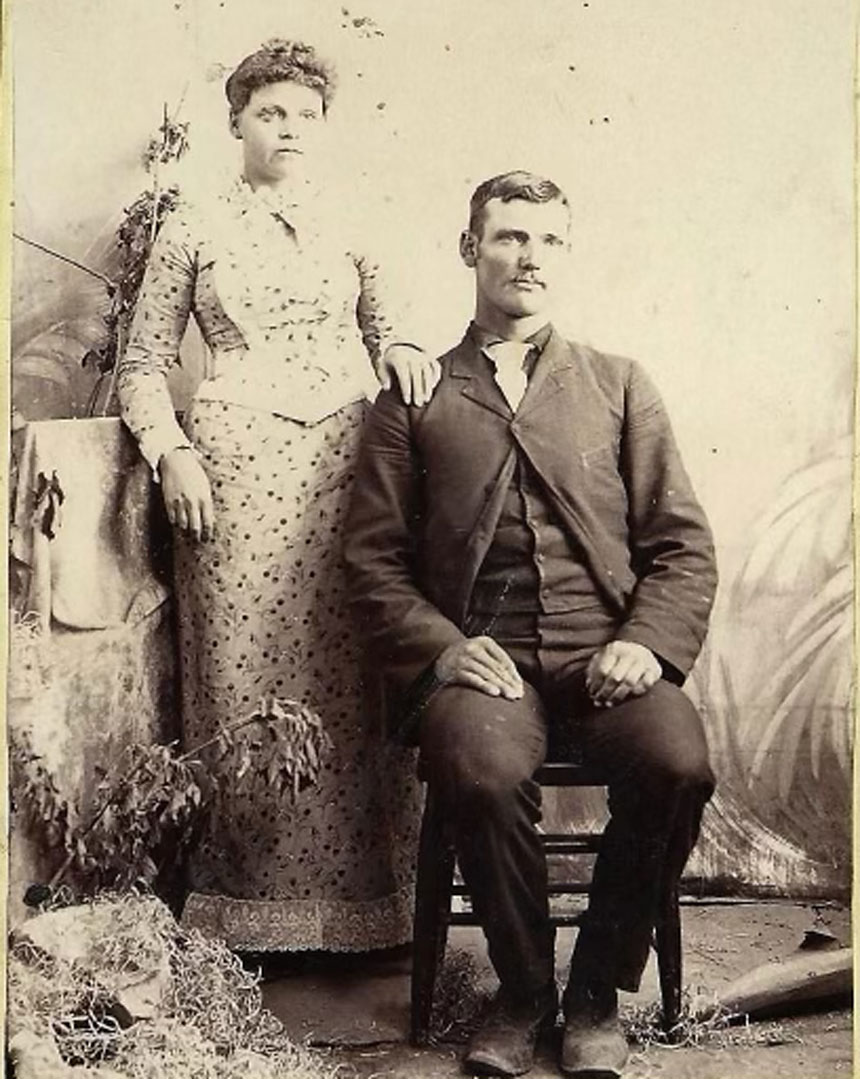

Cyrus and Sarah were married in December 1888 and homesteaded the cabin they had built. They eventually had two children — Arthur and Myrtle.

In the early years of their marriage, Harrop says Cyrus capitalized on the area’s abundance of water by pioneering an irrigation method still used by farmers in the area today.

“Before the Palisades Dam was built and the levees along the Snake River, there was a lot of hollers (ditches) through this country and water ran through most of them year-round. He (Cyrus) was the first one that dug a ditch to take water from a holler to his crops,” Harrop says.

Word began to spread of Rostan’s technique and farmers from Menan, Lewisville, Annis and surrounding areas came to see what he did and how it worked.

“My Grandma Rostan wrote in her family history this was the inspiration for the … dry bed system that we have today,” says Harrop.

Growing up in the wild west

Some of Harrop’s stories of the Rostan’s experiences in that old log cabin seem as if they’re taken directly from the scenes of a Western film. He remembers a story his grandmother once told him about Native Americans paying them a visit.

“Her and her brother were just petrified. Her mother would stand right there at the door and offer them bread and pies. She would not let them in the door,” Harrop recounts.

There was another occasion when the Native Americans came by and Cyrus wasn’t home.

“He had built a place on top of the haystack they were to go and hide if any trouble ever happened. (On this particular occasion), Grandma sent them out to the haystack and told them not to come out until they came to get them. They went out there and hid and could see their mother offering them bread and cakes. The Indians got off their horses, took it and left,” Harrop says.

The Rostan’s eventually saved enough money to build a larger house about 50 yards to the west. It was built sometime around 1900 and has people living in it to this day.

Harrop says his Grandma Myrtle lived in the house and he recalls an experience he had while visiting her as a little boy.

“I don’t know why, but she always served two desserts — a piece of pie and a piece of cake,” Harrop remembers. “She said, ‘I want to show you something.’ We walked from that house back to this cabin. We got to the front door and Myrtle said, ‘This is the cabin my brother and I were born in.’ I remember saying, ‘Oh, that’s nice. Can we go back in and have a piece of pie now?'”

Harrop is now 75 and his perspective today is much different. He considers the walls of that cabin “sacred and hallowed ground.”

Preserving a legacy

Harrop was originally planning to complete the project this fall, but he says this will likely be an ongoing project that lasts a year or two. He isn’t sure what it’s going to cost yet.

Ultimately, he envisions the cabin becoming a historical landmark where people come to learn about the Rostans and how they helped settle the area. Once the project is complete, he’s hoping to eventually place a plaque out front containing photos and a history of what they accomplished.

“I believe with all my heart it will impact our posterity for generations to come,” he says.

EastIdahoNews.com comment boards are a place for open, honest, and civil communication between readers regarding the news of the day and issues facing our communities. We encourage commenters to stay on topic, use positive and constructive language, and be empathetic to the feelings of other commenters. THINK BEFORE YOU POST. Click here for more details on our commenting rules.