After a fire and an election loss, Pocatello school leaders consider running another bond

Published at

POCATELLO — Seven months after a fire destroyed part of Highland High, and weeks after voters denied a bond measure that would’ve restored and improved the school, education leaders are still seeking a way forward.

And they’re grappling with difficult realities — a return to a fully-functioning school is years away, and Highland’s freshman class will never learn in a fully rebuilt school.

“No matter what we do, those kids’ entire high school careers will be in a fractured facility and a fractured environment,” Jena Wilcox, an assistant principal at Highland, said.

RELATED | $45 million bond to rebuild Highland High School fails in Pocatello/Chubbuck

Pocatello/Chubbuck trustees and administrators discussed next steps at a special meeting Tuesday, and seemed torn about whether to put another bond on the ballot. On Nov. 7, their $45 million bond failed with 56% support, short of the needed two-thirds supermajority.

No decisions were made, but the school leaders’ conversation reflected the difficulties of financing major building upgrades through voter-approved bonds, and while navigating laws that hinder their ability to communicate with voters.

Trustees’ next chance to put a bond on the ballot is in May, and they would have to make a decision and submit ballot language by late March. But at least one trustee opposed the idea.

“I do not believe that another bond will pass,” Trustee Angie Oliver said. “So if that doesn’t pass, are we going to do another one? I mean, how long are we going to put this off?”

Students need a fully-functioning school as soon as possible, she said.

But Trustees Deanna Judy and Heather Clarke said they were in favor of another bond election.

“We have one opportunity from this tragedy to do it right,” Judy said.

The insurance monies will pay to rebuild the school exactly as it was, as well as some improvements if current building codes call for them. But Judy said the district should build an improved school that reflects today’s needs, as opposed to the needs of Highland students in the 1960s, when the school was built. At that time, the school didn’t serve freshmen, as it does now, or offer women’s sports.

“We need to change the messaging and educate people on why we need that upgrade. It’s not just to make it bigger and shinier, it’s opportunities for the kids,” she said.

Wilcox expressed support for a second bond election.

“I’m in favor of us trying to do this again and do a better job at it,” she said. “But if we can’t get this passed this next go-around, we have to cut our losses … We have to minimize that impact for kids.”

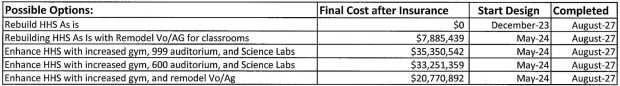

Leaders discussed a few options Tuesday, ranging from rebuilding Highland as it was before the fire, to rebuilding and improving its gym, auditorium and science labs. The price tag for those options range from no cost, to $35.4 million.

If the district’s proposed $45 million bond had passed in November, a chunk of it would’ve gone to a second school, Century High, to improve its gym facilities.

Trustees also discussed whether to give voters a chance to fund just Highland’s improvements on the next ballot.

Results from a recent community survey indicate that the added ask for Century was a primary reason for denying the bond.

And there was frequent discussion about how to better communicate with stakeholders if trustees run another bond ask. More than 300 stakeholders who took the poll called for more public meetings and information.

But Courtney Fisher, the district’s director of communications, said laws constrain outreach efforts.

A law passed last spring, for example, requires districts to post the official ballot language — which is cumbersome legalese — whenever they mention a bond measure or even remind community members to vote. Fisher said the bond language confused constituents.

District officials are also barred from advocating for bond or levy measures, and can only inform or educate. Because of that, Fisher said she opted not to go on radio or television, which kept her from reaching a potentially wider audience.

“We need to help our legislative delegation understand that these legal ramifications are not helping create a more informed electorate,” Fisher said. “It’s causing confusion. People want simple, straight answers, and some of these legal constraints prevent us from doing that.”

Originally posted on IdahoEdNews.org on December 1, 2023